For AI to genuinely change executive search, it will not be through better note-taking, calendar booking, or interview scheduling. Those improvements are useful, but they are incremental.

A real step-change only happens if AI can address one of the core problems executive search exists to solve: finding the right people for a role.

At senior levels, this is not a simple search or retrieval exercise. It is a structured, feedback-led process that starts with translating a brief into a viable search strategy, executing that strategy across complex and imperfect markets, incorporating feedback, refining candidate populations, and forming a view of relevance before deciding on the priority list of candidates to engage. That work typically takes weeks of research, iteration, and judgement.

The opportunity for AI is not to bypass that thinking, but to replicate it consistently and at speed.

When the mechanics of market mapping, job title interpretation, candidate population building, and reporting can be compressed from weeks into hours while preserving the quality of decision-making that experienced search professionals apply, the impact is structural. It improves margins, increases delivery capacity, reduces execution risk, and creates meaningful differentiation.

This does not imply that executive search professionals are being replaced. In practice, the opposite is true. As the heavy lifting of data interpretation and population building becomes faster and more reliable, value concentrates more sharply in human judgement, trust, and relationships. These are the elements of search that technology cannot replicate.

The central challenge, then, is not whether AI should be used in executive search, but how. More specifically, how can consistent and reliable meaning be extracted from messy professional profiles so that individuals can be identified, grouped, compared, and refined in the same way experienced researchers already do, but at far greater speed and scale?

This article explains how Savannah has approached that challenge, why it is far harder than it first appears, and what we have learned by working on one of the most technically demanding problems in executive search.

Executive search feels like an art, but it’s actually a system

There’s a widely held belief that executive search is more art than science. Knowing who the “right” people are for a role is primarily about instinct, experience, and judgment.

Judgement is fundamental. But beneath that judgement sits something far more structured.

At its core, executive search is the repeated act of converting a wish list — a brief — into a sequence of inclusion and exclusion decisions. Out of hundreds of millions of professionals globally, who are the 50 or so people that plausibly fit this role, in this context, at this point in time?

That “billion to fifty” problem is what researchers, in-house teams, and search firms work on every day.

Whether consciously or not, they are applying a consistent set of filters and heuristics to do this. The question is whether that structure is explicit, scalable and programmable.

What makes it hard to find the right people?

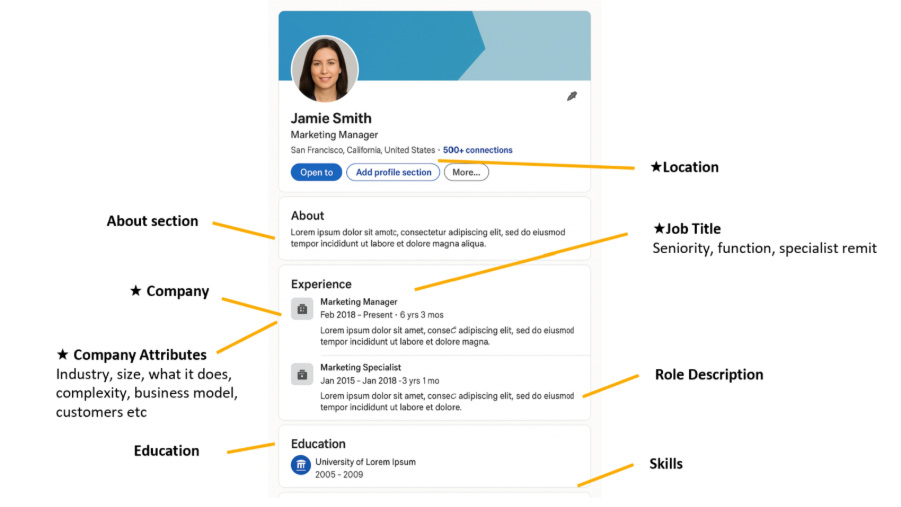

The first question is: which parts of people’s public profiles can be considered accurate, and which can’t?

The ★ symbol indicates the most reliable signals to guide decision-making.

Some data points are binary and reliable: location (current and historic) and companies worked at. Some are contextual but still strong: seniority progression, tenure, industry exposure, company characteristics (size, regulation, B2B/B2C, etc.). Others are weaker: self-authored summaries, skills lists, free-text keywords.

Keywords are indicators, but they’re inconsistently applied, frequently incomplete, and often inflated. In many sectors (professional services, consulting, legal), profiles are not keyword-rich at all.

If you step back, three attributes dominate early-stage relevance decisions: Where someone works, which companies they’ve worked at previously, and what roles they’ve held.

Location can be standardised. Company data can be enriched.

Job titles are the hard part.

Why job titles are such a fundamental challenge

Job titles look simple, but in this context, they aren’t.

They vary wildly by company, industry, geography, and seniority. Two people with the same title may be doing entirely different jobs. And yet, job titles remain the most compact signal of functional experience, scope, responsibility and career trajectory.

If you can’t reliably understand and group job titles, everything downstream degrades. Search becomes keyword-heavy. AI models have to reason over vast amounts of noise and precision collapses. This is why most recruitment platforms lean so heavily on user-generated Boolean logic. It’s an implicit admission that system-level job title understanding hasn’t been solved.

There is often an assumption that large language models should already be able to solve this problem. In practice, they struggle with it for structural reasons. LLMs are optimised for probabilistic language generation rather than deterministic standardisation, which makes them poorly suited to enforcing consistent categorisation across very large datasets. At the scale of tens of millions of unique job titles, this leads to fragmentation, where the same role can be assigned to different categories across runs, even with temperature settings reduced to minimise variation. This behaviour is not a flaw in the models, but a consequence of how they are designed.

What the AI system Savannah built (MapX) does differently to find the right people

We approached job title classification by treating it as a translation problem rather than a prediction problem. Instead of trying to infer relevance directly from free-text profiles, we built a structured functional framework and trained our system to translate the thousands of different ways organisations describe roles into a consistent set of functional and specialist categories. We built a highly detailed framework of 19 functions and 420 subcategories to categorise titles into. The system then uses learned patterns from a large, manually labelled set of real job titles to make an initial classification, and then applies contextual reasoning where titles are ambiguous, taking into account factors such as company type, industry, and career progression. The result is a reliable way of grouping people by what they actually do, rather than by how their role happens to be described, making large-scale search and comparison both faster and more accurate.

The result: 32% more accurate than using state of the art LLM systems alone

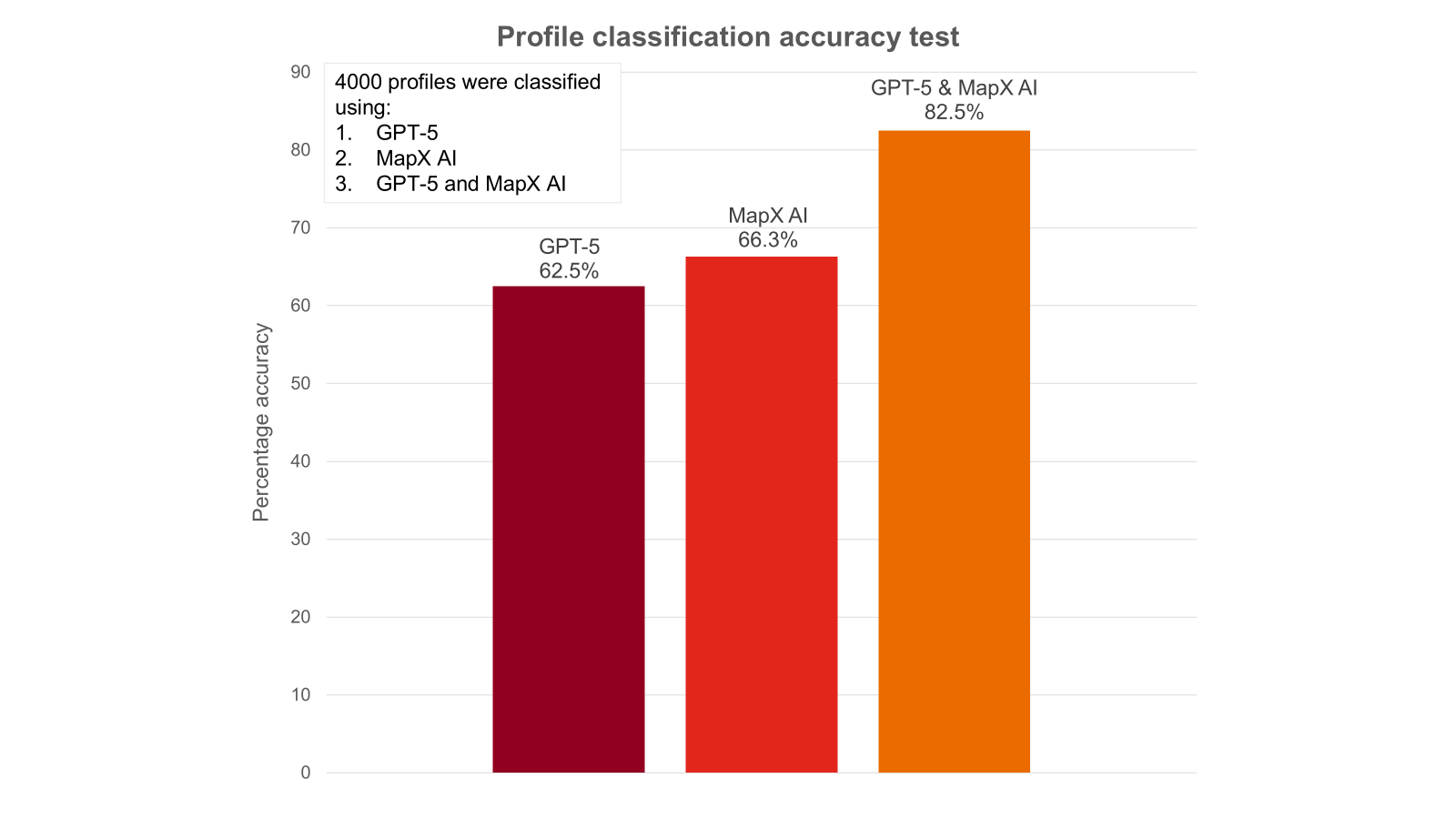

In late 2025, we ran a comprehensive test to understand how effective Savannah’s MapX system was in accurately identifying relevant candidates against a brief compared to commonly used approaches.

We built a ground-truth dataset of 4,000+ job titles, spanning all functional areas, multiple seniority levels, the 500 most frequently occurring job titles globally, and a long tail of ambiguous roles. Each title was labelled in context, based on analysis of the individual’s entire professional profile, not the title string alone.

We then categorised these 4,000+ job titles using three different methods to compare accuracy:

We tested:

- LLM only (GPT-5)

- Our NLP model only – BERT + rules (MapX)

- The combined approach (GPT-5 and MapX)

The results of a comprehensive test on MapX versus other methods for identifying the right candidates

MapX and GPT-5 working together were 32% more accurate than GPT-5 only. Or to put another way, the combination of MapX AI’s translation layer with GPT-5 delivers 53% less classification errors compared to GPT-5 alone.

These results show the significant positive impact of embedding an accurate job title translation layer. Without this, even the most advanced graph or neural system is built on weak initial data.

What does this result mean for executive search?

Building a high-performing job title translation system which works alongside dynamic candidate profile analysis paves the way for significant positive changes in the executive search industry.

Savannah is already experimenting with Agentic AI on several potential use cases. For example:

- conversational talent mapping, where intent is clarified through dialogue

- adjacent and multi-path searching across non-obvious career routes

- dynamic weighting of attributes as priorities change

- identification of genuinely transferable candidates, not just title matches

This capability provides the opportunity to improve solutions for:

- assessment and psychometric grouping

- compensation benchmarking

- organisation design and workforce analytics

- job architecture and role comparison

As desk research cycles speed up, the increased speed in information transmission (from weeks to understand a market to hours and then minutes) creates enormous possibilities. Businesses can quickly investigate multiple possible leadership talent strategies. They can benchmark their leadership against the market and key competitors, quickly seeing what skills and experiences are common or rare, informing buy versus build succession plans. Search firms can more accurately estimate how easy or difficult it will be to deliver on an assignment and price accordingly. Businesses can test different markets, discuss potential profiles and align on what they want and, more importantly, what the market can deliver.

This technology provides new scope for elevating executive search relationships to become truly strategic, partnering on shaping talent strategies, developing deeper levels of trust and enabling more effective account development and expansion.

The breakthrough isn’t a single model. It’s building the interface that makes finding the right people a solvable problem at scale.

That’s what MapX does. Without the MapX translation layer, AI in executive search remains a helpful assistant. With it, AI becomes a system that can reason, adapt, and scale, with significant implications for the industry at large. Contact us to hear more.