Download the full report here >

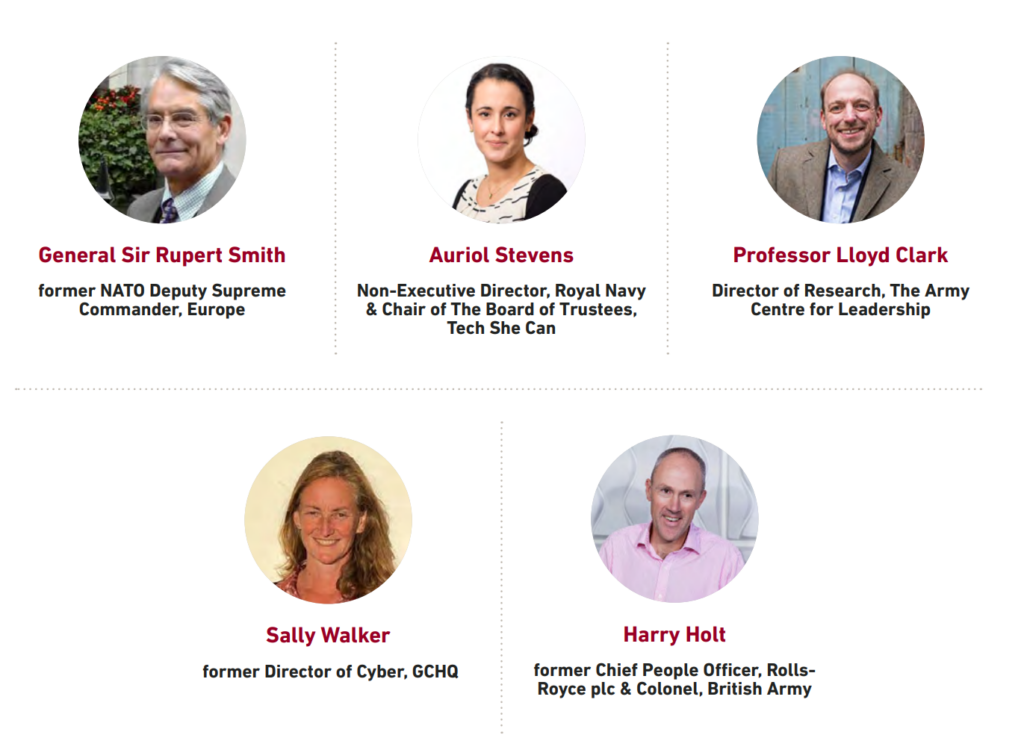

To unearth these insights, Savannah Group’s Next Generation Leadership Institute has assembled a high-ranking panel to set out the defence sector’s unique understanding of how the best leaders are found and enabled. Those panellists come with experience of the top echelons of the British Army, the Royal Navy Board, UK Special Forces, GCHQ and the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst.

General Sir Rupert Smith is one of Britain’s most-experienced military combat leaders. He commanded the UK armoured division in the first Gulf War and led UN forces in Bosnia. Trust, he says, is the essence of military leadership. “You can say all you like on the barrack square but when you’re going up the hill and

someone’s shooting at you, then they’ve got to trust you.”

Unlike a commander, a leader will physically accompany his troops. “You’ve got to be actually in front of the people you’re leading,” he says. “They trust that [the leader] knows the method to get to the objective. That he will look after them on the way to the objective. That he will not be careless of their lives. ”Such a leader should be competent, consistent, decisive, unbiased and concerned for the people they lead.

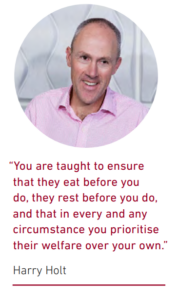

Harry Holt had a highly distinguished military career with U.K. Special Forces before joining Rolls Royce as a Government Relations Officer and ending his 10 year career there as Chief People Officer. He espouses the concept of “servant leadership”, whereby military officers attend to the welfare of those they lead. “You are taught to ensure that they eat before you do, they rest before you do, and that in every and any given circumstance you prioritise their welfare over your own.” This principle of “getting the best out of the team that you lead”, applies equally in business. “People are still your most precious commodity.”

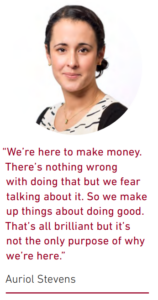

Businesses will struggle to succeed if they do not emulate the armed forces in having clarity of purpose, says Auriol Stevens, a non-executive board member for the Royal Navy. Stevens, a senior executive at IT company Kyndryl who formerly worked at Unilever, says companies can confuse their purpose by creating a “strap line or mission statement” that conceals their commercial imperative. “We’re here to make money. There’s nothing wrong with doing that but we fear talking about it. So we make up things about doing good. That’s all brilliant but it’s not the only purpose of why we’re here.”

General Smith and Harry Holt also identify areas where business could sharpen its leadership by learning from the military. In explaining the philosophy of Mission Command, General Smith says that a culture of devolved decision-making is essential to gaining speed and advantage on the battlefield. In the commercial world, he says, crucial decisions are invariably delayed by the need for preliminary conversations. “My brief observation of the last 20 years of business and commerce is you have meeting after meeting because nobody’s in charge.”

Holt echoes the need for an “organisational structure that is as flat and fast as possible”, particularly in moments of crisis. “Most businesses think they’re doing well if they get eight layers between the chief executive and the shop floor,” he says. “It may be fine for managing the company on a day-to-day basis. But in times of crisis or rapidly changing circumstance, I would advocate maybe collapsing some of those layers to create something that is flatter and faster.” If a leader truly believes in the idea that “knowledge is power”, he says, “you need to empower your people by sharing that knowledge with them”.

Leaders do not come out of a mould. Sally Walker, the former Director of Cyber at the UK’s GCHQ intelligence agency, describes how she oversaw the creation of the National Cyber Force by championing cognitive diversity and bringing together people of very different backgrounds… “It was the mix and their

contribution that really mattered but, my goodness, it was challenging every day to make sure that as an organisation we focused not on what people looked and sounded like, but what they were thinking.” The current head of GCHQ, Sir Jeremy Fleming, calls it “the right mix of minds.”

The key strategy is “to ensure that everyone in the room is willing to speak up”, says Walker, who now runs the AI company Human Digital Thinking. The leadership relationship between the military and business is a two-way street. Stevens also advocates a more outward-facing approach in the military, commending the US Navy for “bringing in leaders who haven’t come through the ranks” and have accrued different leadership experiences.

Professor Lloyd Clark, Director of Research at the Centre for Army Leadership, based at Sandhurst, says the Army long recruited its leaders from “a certain social background” and believed it “had nothing to learn from any other sector”.

Only recently has it come to a realisation that it must incorporate leadership expertise from outside the military. “We are learning from business, we are learning from sport and from other organisations,” he says. To this end, a new British Army Generalship course has been created, exposing potential battlefield leaders to insights from business CEOs. An NCO Academy has been set up, teaching leadership principles. “We must never stop learning,” says Clark.

The Army, an organisation historically based on hierarchy and following orders, is now embracing with the concept of “intelligent disobedience” and finding room for the “disruptors and mavericks” who create a “challenge culture” and can have a positive impact on leadership. “I’d like to see more of them in the Army but again there is that tension between those individuals and the culture.”

According to Holt, the former Special Forces and Rolls Royce leader, there is a common need across business and the military to blend a culture of creativity with a respect for regulations. No tourist wants the turbine blades on their holiday aircraft to be redesigned by a machinist who that morning “came up with a completely innovative and agile way of doing it,” he points out. “What you need, and this is tough, is a degree of what I call organisational schizophrenia, where people know the areas where they need to stick to the process – or the drill in a military context – and the areas where they’re absolutely encouraged and empowered to innovate and to be creative.”

In war and in business, leaders who fail to adapt are lost. “There’s nowhere where circumstances change quicker than on the battlefield,” says Holt. “So it’s not surprising that the British Army, particularly the Special Forces, spends a lot of time preparing its people to adapt to those changing circumstances quicker than their adversaries. But the same is true in business. Maybe circumstances don’t change quite so rapidly, but they change very profoundly. And it is absolutely the case that those that change fastest tend to prevail.”

The Panel